Thinking beyond middlemen elimination for increasing farmer income

Eliminating middlemen is often considered the most effective way of increasing farmers’ income. Theoretically, it is correct. The farmer gets only 50–70% of what the end consumer pays for the produce. The farmer is the one who puts his blood and sweat for 4 to 6 months to grow the produce, and these middlemen take a big piece of the pie just like that. This sounds unfair, and even frustrating at times. With the advent of technology, a lot of start-ups and even conglomerates have tried to break this chain by directly connecting the farmer to end consumers. Though a lot of such initiatives have gained traction, their net impact is minuscule. Ninjacart used to do handle 1500 tonnes of fresh produce every day (the highest volume handled by any start-up in India) and that was less than 0.01% of the total volume.

Why is it so difficult to eliminate these middlemen?

The strongest link in the chain is the market vendor, who collects the item from the farmer and sell it in his Mandi located in the market. With many such vendors, the market acts as the aggregation point of supply and demand, where prices reach their equilibrium. Each vendor adjusts his selling price over the course of the day based on his availability of stock and the progress of the sale. Market dynamics take its course and no one really has control of the prices.

The basic approach of any firm is to increase the sales while bringing down the unit cost and hoping to make it unit profitable at some point. Generally, the engine slows down at the volume much before the break-even point. With prices always lying in a range in the market, farmers would always demand the higher end and customers would always demand the lower end of the spectrum. It will not be possible to capture the entire value sunk into the market, because there is no single reference price. Bringing down operating costs isn’t easy as well. The market is always efficient in terms of transport, labour and dump. Economies of scale have very minimal impact on these cost items. It is definitely one of the toughest and most complex supply chains that exist. It takes an enormous amount of effort and resolve to run such a business.

While I admire and applaud everyone who has attempted it, it is easy to get lost in the storm and not seek a way out. I would like startups and firms to re-look at the Agri landscape with a fresh perspective and explore alternate ways to create an impact.

Framework for alternate themes:

Below is a simple matrix where each line item involving farmer’s income is bucketed based on the scope to improve and impact on income.

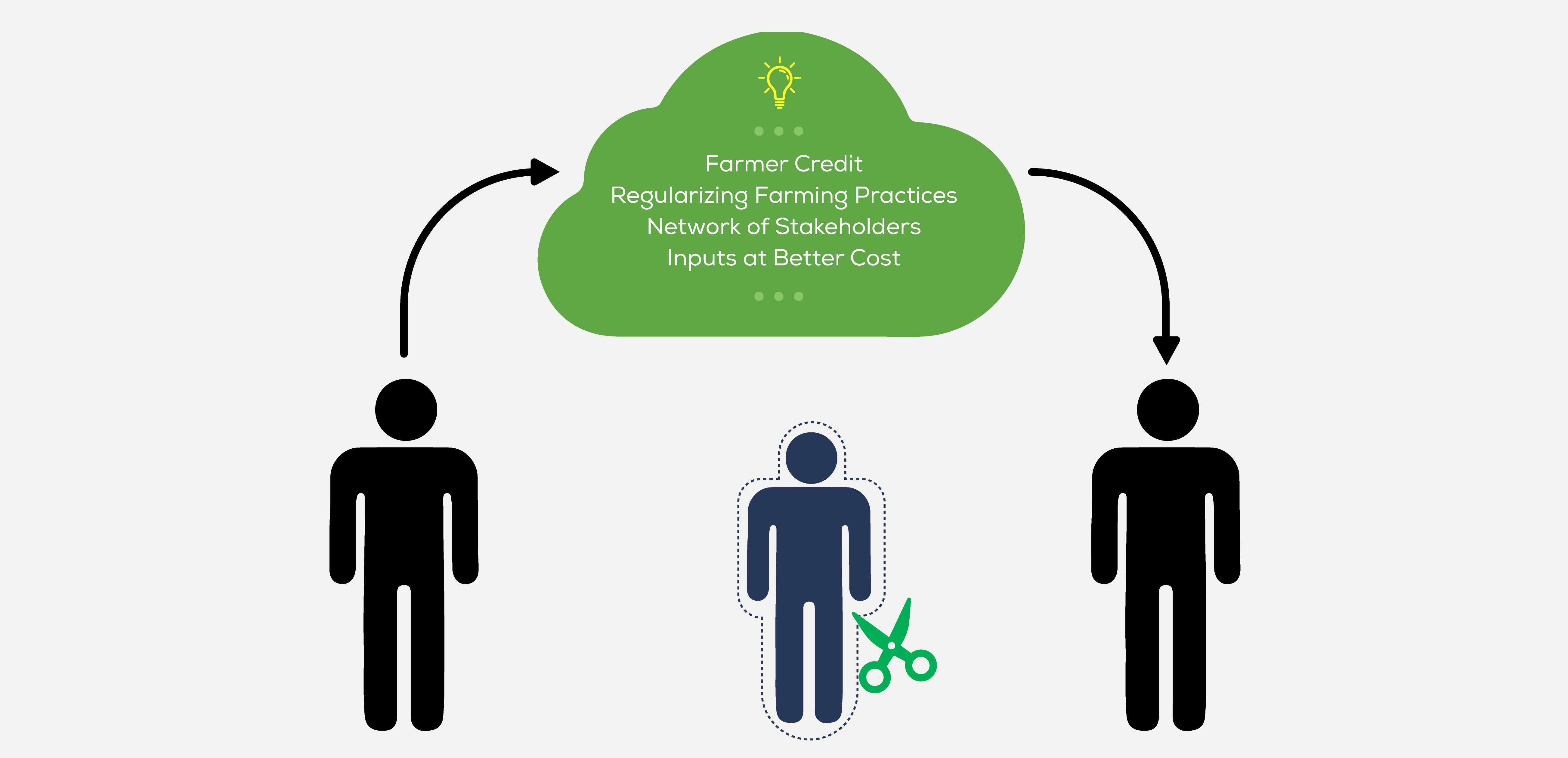

Potential ideas and initiatives can be grouped into themes as below:

1. Organizing Farmer Credit: (Sell to multiple local market vendors & Cost of credit)

The cash structure of agriculture and poor financial planning of farmers leads to the working capital debt crunch during the growth phase of the crop. Though the government has mandated banks on the minimum crop loans, higher service cost, inability to track end usage and lack of visibility on cash in-flows make Agri loans a dark zone for the banks and other NBFCs.

Credit is the most common tool used by vendors for farmer retention. Credit comes in various forms like direct cash, providing seeds and fertilizers etc. The farmer doesn’t just owe the money, but is also forced to sell his produce to that vendor (often termed as the first right of refusal to the stock). Few vendors exploit these farmers by deducting more wastages and paying less than the realized price. The farmer is literally stuck with that vendor for the particular season. Since the farmer has used up part of that season’s harvest money to pay existing debt, he is forced to again get a loan for the next cycle as well. A farmer gets stuck in this credit cycle, similar to someone being stuck in the cycle of credit card bills.

Freeing up the farmer from this credit hook will protect him from both, exploitation on output products and also exorbitant interest rates. Formal credit at nominal rates and guidance in financial planning is an effective way to bring a farmer out of this credit loop and operate independently. This has the potential to reduce credit cost by 10% (4% of sale value) and increase per kg price by Rs.1 /kg (5% of sale value), resulting in a total increase of 9% of sale value.

2. Formalizing network of stakeholders: (skip the local market and sell to distant markets)

In areas of high agricultural supply, it is common that the stock is aggregated in a local market (which charges a commission) and forwarded to a distant market. It is possible to directly send the stock from farm point to destination, skipping the local market and thereby saving its associated costs (commission, labour and transportation charges which sums up to 10 to 15% of sale value). Generally, less than 10% of long-distance trade happens directly from fields. Aggregators’ fears of payment default and destination market vendors’ fear of quality deviations are major hindrances. Local market vendor provides credit risk control, quality assurance and consistent supply which makes them a stable option; and destination vendors are ready to pay that additional 10–15% cost for that stability.

It is true that there are many such defaulters operating in each market. These guys identify new people, do a few transactions and run away with a huge credit amount. But there are a handful of genuine vendors in each market who can be trusted with payments and correct price realization. If we could identify and find such vendors in the destination market and provide quality assurance at farm point, it can bring more stability in direct farm to destination market transactions. This has the potential to increase margins by Rs.1.5 to 2 per kg (7% of the sale value).

3. Build a connect with farmers and regularize farming practices: (Increase selling price, yield and quality of produce)

Horticultural farming is definitely a profitable business in the year-long run. The yearly average of a farmers’ in-hand is Rs.12 to 15 /kg and cost of the product is Rs.5 to 8 /kg. Every year there will be a month where prices hit the roof and also a phase where it crashes to the floor. When a farmer has taken credit during growth and his peak harvest falls in the low-price phase, he won’t be able to repay the debt and gets stranded for the next season. Part-time farmers are always at risk of such situations. Though it is not possible to exactly predict the peak and crash phases of the market, it is possible to identify 3 to 4 months windows through price and supply trends. Farmers can be assisted with making the right choice of crop to best avoid the price crashes and plan the yield during peak season. This can increase farmers’ in-hand by Rs. 3 to 6 per kg (15% of sale value). It will be difficult to make the farmers believe in your suggestion and plan their harvests. Since it is an indirect value addition, monetizing the additional revenue also will be a tricky thing.

4. Inputs at better cost through consolidation: (Fertilizers & Pesticides, Insecticides)

Fertilizer and pesticides are heavily subsidized and closely tracked by the government as it directly impacts the food production and inflation of the country. Retailers have to record all the sales to avail the subsidy from the government. Most of the ERP and billing solutions used by retailers and dealers are age-old desktop-based products built for accounting purposes, which are priced at Rs.10K-40K per year. New mobile-based billing solutions with better features and lesser costs will attract a good volume of retailers and dealers. Once retailers and dealers start punching their sales, their demand can be consolidated and routed directly from the Manufacturer or CnF agent at a lesser cost and higher expiry date. This can reduce inputs cost at the farmer end by 5% (2% of sale value).

Instead of trying to digitize the entire agri-ecosystem end to end, firms can focus on identifying a strong entry point for technology. Then they can slowly capture more of the value chain by gradually moving up or downstream. Even though so many startups have ventured into this space, there is still space for digitization in the Agri ecosystem. With the stakeholders being ‘not-so-technology-friendly’, whoever brings this change will enjoy great market leadership and loyalty for a long duration. It is not going to be easy, but it is definitely worth the effort and investment.

Note: All ideas and data are from my personal experience and judgements. I will be happy to hear more ideas or any corrections in my view. You can reach out to me at chockalingam.j@ninjacart.com or DM me on LinkedIn.

We welcome all tech or product minds who want to join us in our journey to transform one of the biggest and toughest business networks in the world.

Interested people can send their resume to chockalingam.j@ninjacart.com or apply directly at the below links :

Product / Senior Product Manager

Written By

Chockalingam J

Senior Product Manager

0

No Comment! Be the first one.